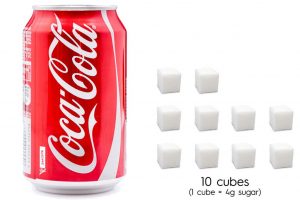

There are strong links between excess sugar consumption and major health issues such as tooth decay, diabetes and obesity. In recent news Coca-Cola and Pepsi have vowed to slash their use of sugar by 20 per cent over the next seven years. Read the full article sourced from Sydney Morning Herald or continue reading below.

Source: Sydney Morning Herald

The country’s biggest soft drink makers including Coca-Cola and Pepsi have vowed to slash their use of sugar by 20 per cent over the next seven years in a bid to tackle Australia’s obesity epidemic.

But the highest-sugar varieties of drinks such as Coke will remain unchanged, with the plan largely focusing on efforts to produce and market low-sugar alternatives, and reduce serving sizes.

The pledge, announced by the Australian Beverages Council on Monday, has also been criticised as an attempt to stave off a sugar tax by announcing a sugar-reduction target that was already in train.

The council’s chief executive Geoff Parker said the industry would cut sugar content by 10 per cent by 2020, and by another 10 per cent five years later, “without having a negative impact on taste”.

More than 80 per cent of the non-alcoholic beverage industry had signed up to the agreement, he said, including energy drink maker Frucor Suntory and Asahi Beverages, which owns Schweppes.

Health Minister Greg Hunt, who joined the industry for the announcement in Canberra, described it as “in my knowledge, the most significant change in food or beverage formulation in Australia”, and promised it would reduce sugar consumption.

“This is a trend that is and should continue over the course of the coming decades,” Mr Hunt said. Asked if the government would keep pressuring soft drink makers to cut sugar by more than 20 per cent, he said: “We’ll talk in 2025.”

Mr Parker said the move would be “quite costly” and “really hard” for drink manufacturers but it had “nothing to do” with warding off a sugar tax – which has been introduced in Britain and is backed by the Greens in Australia, but opposed by the two major parties.

Mr Parker said the high-sugar versions of drinks such as Coke would “absolutely” still be available. “This is about choice,” he said.

Coca-Cola Amatil managing director Alison Watkins said the company was on-track to meet its existing promise to cut the sugar content across its sales by 10 per cent by 2020, and looked forward to “delivering on today’s pledge as well”.

The company has grown its portfolio of low-sugar or no-sugar drinks, such as bottled water and coffee, in response to a shift in consumer preference away from sugary soft drinks, with sales of its fizzy drinks falling 8.1 per cent by volume over the past two financial years.

CCA has already reformulated 22 products since 2015 to make them lower in sugar, Ms Watkins said, including its popular Sprite and Fanta brands.

Any increase in sales volumes of low and no-sugar drinks – including bottled water – will count towards the beverage company meeting Monday’s pledge, which targets a cut to the amount of sugar contained in every 100ml of drink they sell, rather than an absolute reduction in sugar being consumed from their products.

“It’s about ramping up that reformulation program,” Mr Parker said. “What this announcement does is crystallises what the industry has been doing for two decades.”

A Beverages Council spokesman confirmed progress would be measured from 2015 data and any sugar reductions which have already taken place since then will count to the 20 per cent target.

Greens leader Richard Di Natale said the industry’s pledge was simply “sugar-coating” and “doesn’t go anywhere near far enough to dealing with this public health crisis”.

Australian Medical Association president Tony Bartone said the endeavour was “welcome, but a drop in the ocean” when it came to reducing sugar consumption.

“In some sweet and sugary beverages there is just an enormous amount of sugar and even a 20 per cent drop isn’t really significant in addressing the underlying problem,” he said.

“The sugar tax that we’ve called for has been shown to work in other countries.”

Kathryn Backholer, a senior research fellow at Deakin University’s Global Obesity Centre, said the act of self-regulation must be independently monitored “so that it does not become an empty commitment designed to delay any action on a sugar tax”.